Column

Nurturing international collaborations

Diversity of researchers and staff at ELSI is helping answer important questions about the origin of life

"Our English might not be perfect, but as researchers, we speak the same language, which is science," says mineral physicist Steeve Gréaux, who is from France.

It's an outlook shared by many of Gréaux's colleagues at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI), which employs researchers from all over the world. Approximately half of the institute's researchers are non-Japanese. Researchers came from as far as Argentina, Israel and Bangladesh.

ELSI encourages its staff to collaborate with scientists from different countries and backgrounds, and has gone to great effort to smooth the transition for scientists who visit or move to Japan.

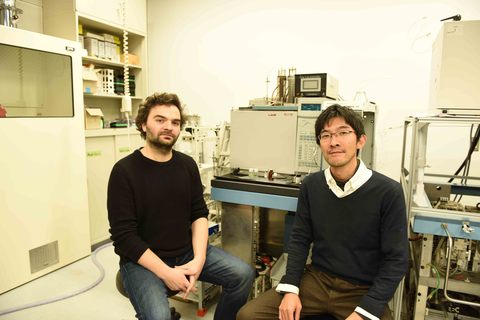

An example is the partnership Gréaux, who is based at ELSI's satellite center in Ehime University, has formed with his Japanese colleague, Shigenori Maruyama, an Earth historian and ELSI PI.

The researchers are interested in the formation of the Earth and are specifically hunting for a particular type of rock, which they believe formed when parts of the early Earth's surface were covered in molten rock more than 4 billion years ago.

While evidence of this rock has not yet been found on Earth, Gréaux and another Japanese colleague, Earth scientist Masayuki Nishi, also based at ELSI's satellite center, have been experimenting to understand what such rocks might look like if they had been subducted deep into the Earth's mantle.

Their team specializes in recreating the high-pressure and high-temperature conditions of the Earth's interior using a device called the multi-anvil press. The group also recruited ELSI lab manager Shigehiko Tateno, an expert in the diamond-anvil cell.

"By combining our expertise, we cover all the fields required to carry out this project," says Gréaux.

"ELSI's promotion of internal collaboration across different fields makes it special in Japan," says Tateno. With so many of its researchers coming from abroad, cross-cultural collaborations are common at ELSI.

Steeve Greaux (right) and Masayuki Nishi at ELSI's satellite centre in Ehime University.

Steeve Greaux (right) and Masayuki Nishi at ELSI's satellite centre in Ehime University.

Connecting people

In the winter of 2015, ELSI brought Renata Wentzcovitch from the University of Minnesota in the United States to Japan to reunite her with her long-time collaborator, Koichiro Umemoto, at ELSI's Tokyo campus. The opportunity meant the Brazilian and Japanese quantum physicists could hash out the text for their recent publication in which they provide a unified view on the volume isotope effect in ice. The paper explains why the volume of ordinary ice increases when lighter isotopes of hydrogen are replaced with heavier ones, but the opposite trend occurs in high-pressure ice.

"Communication between us was 'clear of noise'," says Wentzcovitch. "Language? We did not need that. Communication was straight from mind to mind," she says. Umemoto agrees: "In science, I don't feel any differences."

As well as paying for visitors to come to ELSI, the institute sets aside money for researchers to travel and organize workshops, and to send young ELSI researchers overseas to establish new connections. A strong and supportive team of administrators help ease the transition to Japan for foreigners, from helping to find an apartment to translating grant applications.

It takes two

Great partnerships often form when one party has something another group needs. It didn't take long for French analytical chemist, Alexis Gilbert (now working at the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Tokyo Tech) to pair up with geochemist, Yuichiro Ueno, soon after joining ELSI three years ago. "I had a solution to his problem, and he had a problem to my solution," says Gilbert. Alexis has developed a method for determining the chemical processes that can give rise to organic molecules, which Ueno is using to prove that such chemistry is possible in hydrothermal vents -- suspected by some to be the first source of life.

Collaborators Yuichiro Ueno (right) and Alexis Gilbert at the ELSI lab.

Collaborators Yuichiro Ueno (right) and Alexis Gilbert at the ELSI lab.

"ELSI allows a lot of time and space for meeting people," says Gilbert, referring to its large and small common rooms, lunch talks, seminars, and monthly ELSI-wide meetings. "Everybody knows more or less what the other researchers are doing," he says.

It is these kinds of daily interactions between researchers from different backgrounds and disciplines that helps ELSI gain insights into some of the major scientific quandaries it has set out to understand.