ELSI Blog

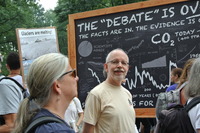

67 People's Climate March

Last Sunday, the largest climate march in history took place in New York. On September 21, 2014, more than 400,000 people gathered on the Upper West Side in Manhattan to demonstrate. My wife Eiko Ikegami and I were two of them. We were very lucky: while others came in by buses and trains and cars, we happened to live only a few minutes walking away from the start of the march. The pictures included here were taken by Eiko.

Last Sunday, the largest climate march in history took place in New York. On September 21, 2014, more than 400,000 people gathered on the Upper West Side in Manhattan to demonstrate. My wife Eiko Ikegami and I were two of them. We were very lucky: while others came in by buses and trains and cars, we happened to live only a few minutes walking away from the start of the march. The pictures included here were taken by Eiko.

The march was a demonstration of sorts, but unlike most demonstrations it was not for or against any particular measure or goal. It was more an attempt to raise a larger awareness of the way human activities are now affecting the state of the environment in totally non-sustainable ways, depleting resources at a rapid rate, affecting the quality of air and oceans, with many side effects, including climate change. The political dimension of the march was to influence policy makers, who in a democracy are dependent on large numbers of voters in order to stay in power. And without staying in power they won't be able to change policy, no matter how idealistic or scientifically accurate their motivations may be. So the hope was to show as broad a base as possible for the concern that many individuals have, that not enough is done by politicians to care for the future of the planet.

The political dimension of the march was to influence policy makers, who in a democracy are dependent on large numbers of voters in order to stay in power. And without staying in power they won't be able to change policy, no matter how idealistic or scientifically accurate their motivations may be. So the hope was to show as broad a base as possible for the concern that many individuals have, that not enough is done by politicians to care for the future of the planet.

But in order to make a convincing clarion call, the science needs to be sound too, of course. And while computer simulations to predict the future of our planet always carry uncertainties, those simulations can be tested to a significant extent by postdicting the past: starting with the inferred state of Earth some time ago, calculting forwards, and comparing the results with observations at a later time, less long ago. This is what connects the Climate March with what we are doing at ELSI, where we are studying the way the climate, and more generally the whole state of our planet, changed over time. In addition, we are studying the way climates are different on other planets in our solar system, as well as in other planetary systems, around stars other than the sun. The more we know about why the climates on different planets are in the different states they are in now, the more we will be able to get a sounder understanding of how our own tinkering with the conditions on Earth may affect how things will change over time.

This is what connects the Climate March with what we are doing at ELSI, where we are studying the way the climate, and more generally the whole state of our planet, changed over time. In addition, we are studying the way climates are different on other planets in our solar system, as well as in other planetary systems, around stars other than the sun. The more we know about why the climates on different planets are in the different states they are in now, the more we will be able to get a sounder understanding of how our own tinkering with the conditions on Earth may affect how things will change over time.

We may not think every day about the future of the Earth, while we are carrying out our research at ELSI, but it is good to remind ourselves about the responsibility we have, collectively as scientists, and in particular planetary scientists, to present to the public as clear a picture as we can about what we know and don't know about climate change, based on our exploration of Earth and other planets. There was plenty of time to think about all this, since it took more than two hours for our part of the line to even start moving. Getting almost half a million people funneled through a single route in Manhattan is not trivial. While waiting, as astronomers tend to do, I made a few quick order-of magnitude estimates. At first I guessed from the length of the waiting line, starting at Columbus Circle and stretching to 86th Street, plus the fact that people were still milling around, accreting from neighboring streets, that there were at least about 300,000 people, and soon it became clear that because people kept streaming in, the total might well be growing further.

There was plenty of time to think about all this, since it took more than two hours for our part of the line to even start moving. Getting almost half a million people funneled through a single route in Manhattan is not trivial. While waiting, as astronomers tend to do, I made a few quick order-of magnitude estimates. At first I guessed from the length of the waiting line, starting at Columbus Circle and stretching to 86th Street, plus the fact that people were still milling around, accreting from neighboring streets, that there were at least about 300,000 people, and soon it became clear that because people kept streaming in, the total might well be growing further.

So taking a somewhat larger number, like 400,000 (later indeed reported: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/21/peoples-climate-march_n_5857902.html) I figured that while standing still, you could pack people at 40 in a row, adjacent rows half a meter apart, which would take up 5 km. But when such a packed group starts walking, rows are more likely to be a meter apart, with an total length of group of 10 km. So this means that the front of the line would have to walk 5 km before the back, where we were, would even start moving. While a typical walking speed is 5 km/hour, getting a crowd like that to move will succeed at most at half the regular walking speed, which would mean that it would take two hours for us to get out of our starting blocks. So I wasn't surprised that it indeed took about two hours before we were finally underway. Orders of magnitude estimates are actually useful in daily life!

During this waiting time, I suddenly heard somebody call my name: it turned out to be Cameron Smith, one of the MOL workshop participants, who visited ELSI in July. Estimating that I probably saw a few thousand people around me, while stretching my legs and walking up and down a bit along the side lines, I made the astronomer's extrapolation, based on an observation of only 1 event, that there might be at least a 100 people I knew in the march -- a reasonable probability, given that I know a few hundred people in Manhattan and that perhaps one in a few was there. So meeting Cameron was enough to convince the astronomer in me that at least to order of magnitude all was well in terms of statistics -- though other (non-astro) physicists would probably bristle at the size of the error bars associated with meeting 1+-1 colleague. :-)

In an interesting twist of fate, in the evening of the very same day of the march, a NASA spacecraft called MAVEN, launched ten months earlier, arrived at Mars to study . . . climate change! I don't think the organizers of the march had any idea of that, when they decided on the date (it was planned to happen on the Sunday before the U.N. Climate Summit of world leaders, also in Manhattan, two days later). The goal of MAVEN (short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN) is to gather data to allow us to reconstruct how Mars changed from a rather wet and warm place to its current cold and barren condition. The timing couldn't have been better, warning us to be careful in tinkering with the climate of Earth.

And to top it off, two days later India's Mars Orbit Mission (MOM) also inserted itself equally successfully into orbit around Mars, with one of its objectives being to study the Mars atmosphere and its changes over time -- an enormous technical feat, especially so because it was India's first try (the US, USSR, and Europe's ESA all failed on their first try).

As another footnote, concerning the interaction of science and politics, MAVEN almost hadn't made it. Its rocket launch was planned for Nov. 18, 2013. Liftoff preparations were frozen when the government shutdown went into effect on Oct. 1, 2013. For a few aggrevating days, none of the personnel involved in the launch was allowed to show up for work, but then a compromise was made to give MAVEN an emergency exception, well before the end of the shutdown on Oct. 17, 2013. Climate research in the US seems to meet politics at some of the most unexpected corners.

Finally, as a nice and moving touch by some Japanese who were present, there was a 3,000 pound ice sculpture forming the letters "The Future" in front of the Flatiron Building on Fifth Avenue, as I would later read in the news: dripping onto the sidewalk, it had been carved over two days in Queens by a group of Japanese ice sculptors, as a gesture to point to the ongoing melting of glaciers and polar ice caps on Earth.