ELSI Blog

18 For The Love of...Bugs

When I was set to go off to college in New England, congenial Americans would warn me of mainly two things of the region: the capricious weather ("If you don't like the weather now in New England, just wait a few minutes" - did Mark Twain say that?) and the high population of insect life. But point of reference lies in relativeness and I found both warnings to be appreciated in kindness but not amounting to much in reality.

Growing up in Taiwan and coming from Japan where the summers are hot and humid, the insect alert was, frankly, featherweight. But what struck me more than the actual visible bug population (or the lack thereof) was the general American cultural attitude towards bugs. By and large, insects were spoken of more in the language of pests, something which one preferred not to cross paths with, a 'good riddance' affair.

I recently thought about this as I stood in a bookstore flipping through sample entrance exam questions for admissions into selective Japanese junior high schools. I was completely humbled. Pages were devoted to detailed queries on the life cycles of cicada and mantis, spider and dragonfly, cricket and butterfly. I could barely answer even the multiple choice questions.

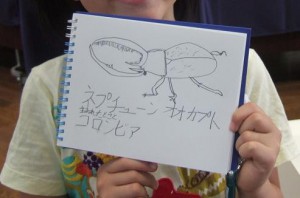

Come to think of it, understanding insects is an integral part of the Japanese elementary school education, much more so than in the international school that I had attended. My son has a whole logbook filled with descriptions and sketches of the stages of different insects' development. As part of their studies the kids are released into the school grounds, themselves like a swarm of hungry locusts, to observe and draw what bugs lay eggs on what plants, what creepy crawlies hang out where at what season. The classroom is often home to a couple of clear cases whose mysterious soil contain some bug at one process or another of breeding or development. These are often prized catches or possessions brought in by students who want to share their topic of fascination.

Once, in 2nd grade, the mascot caterpillar in my son's class inched its way to freedom, finally to be found having entered pupa stage in the most inconvenient of places, the classroom door-frame. Needless to say, that door stayed lovingly propped open, with multiple sets of eyes keeping constant and close watch for the emergence of their class chrysalis. Despite the awkwardness, the teacher and children chose to adapt to bug/nature rather than move it for their convenience.

And when not in school, the love of insects spills into the home. There is a good likelihood that some form of larvae lies dormant in a plastic case somewhere in the Japanese household, quietly awaiting their seasonal debut. I am, in truth, somewhat squeamish of bugs but as part of Japanese parental custom, my son and I have spent two years caring for a colony of singing crickets and their progeny. We were initially given six thumbnail-size chirpers, which we fed slices of cucumber, eggplant, apples, and the occasional dried fish (we read that it lessened the likelihood of cannibalism if we provide alternative sources of animal protein) and religiously misted the soil to maintain ideal humidity.

We enjoyed their loud and loquacious stridulation during summer to fall, a cultural sound that is supposed to distract the Japanese mind from the unbearably hot summer evenings. (My American husband complained that their racket kept him up, thus reminding him even more of the oppressive heat.) When the last of the crickets died, we emptied the soil onto newspaper to collect the eggs that had been laid. These eggs hibernated under the laundry room sink and when the new generation hatched, we passed them on to friends, just in the way that we had inherited our first batch.

I am in no way an exceptionally entomologically oriented parent. I know so many parents and children cultivating far more impressive insect farms, out of their small apartment balconies at that. As adults, we Japanese are not particularly avid outdoor-loving people; in fact, I would say that many of us prefer the comfort of indoors. And yet, our love of insects is so clearly a part of our culture.

For both adults and children, the Japanese seasons are marked by insect-related activities and associations. We enjoy the cacophony of cicadas and crickets, we cultivate our pet rhinoceros and stag beetles, we check out the websites that tell us where best to view fireflies and then go out to enjoy the light show. This interest is galvanized in early education, reinforced by a high standard in basic bug literacy in the curriculum, further inspiring children to be comfortable with bugs. This Japanese love of insects is one of our strongest entry points to our appreciation of nature, to our understanding of environmental issues, and even to our health conscious eating habits.

On this note, I leave you with one haiku, a genre of poetry filled with odes to bugs.

What stillness!

The voices of the cicadas

Penetrate the rocks

Basho

(from Reginald Horace Blyth's Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, 1942)